In earlier posts on the Gospel of Mark, on passages that are proposed by the lectionary during the season of Epiphany, we have seen that Mark tells of the beginning of the good news of Jesus, chosen one, with stories in which Jesus is commissioned for his role (1:12–13), announces his message (1:14–15), and calls people to follow him (1:16–20). It is a strikingly energetic start to his narrative.

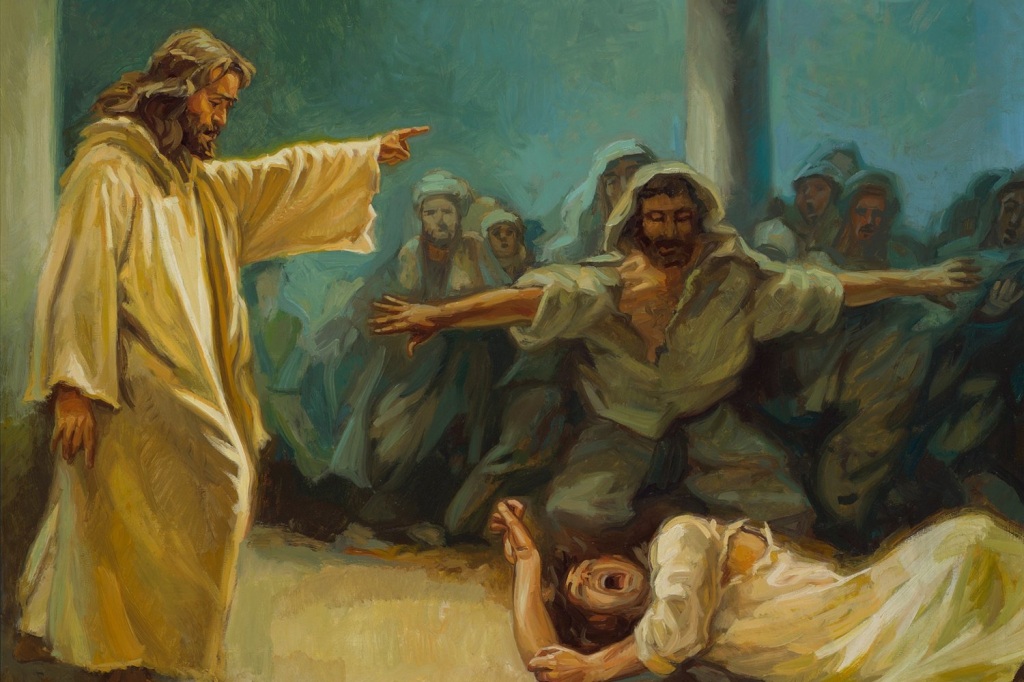

After these scenes Mark takes us to a scene in a synagogue, where he reveals the authority that Jesus had, in calling people, to command “the unclean spirit, convulsing him and crying with a loud voice, [to] come out of him” (Mark 1:21–28). This is offered by the lectionary as the Gospel for the fourth Sunday after Epiphany.

The initial impression of the people in the synagogue regarding Jesus is positive; they were “astounded at his teaching” (1:22). Teaching is one of the key characteristics of the activity of Jesus (4:2; 6:6, 34; 8:31; 9:31; 11:17; 12:14, 35). In Galilee, “he went about among the villages teaching” (6:6); in Jerusalem, “day after day I was with you in the temple teaching”, Jesus tells the crowd in the Garden of Gethsemane (14:49).

However, we have not heard anything of the teaching of Jesus at this early point in Mark’s narrative; detailed teaching will come later, in parables beside the sea (4:1–34), in Genessaret (6:53—7:23), on the road to Jerusalem (8:31–38), in Judea (10:1–16), in the temple forecourt (11:27—12:24), and on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple (13:3–37). This synagogue scene in Capernaum is thus the first glimpse of the power of Jesus’ words.

The polemic that will dog Jesus all the way through his public activities is signalled in this synagogue scene. The people in the synagogue were astounded at his teaching “for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes” (1:22). Those scribes will be seen in conflict with Jesus in subsequent scenes; in Capernaum (2:1–12), in the house of Levi son of Alphaeus (2:13–17), in Nazareth (3:19–35), in Genessaret (6:53–7:23), in Galilee (9:14), and in Jerusalem (11:18, 27). Eventually they join with the priests (1:1) and then with the earlier conspirators, Pharisees and Herodians (3:6) to implement the plot “to arrest Jesus by stealth and kill him” (14:1).

By the end of the scene, the people have become even more convinced; Mark says that they are amazed, and are asking, “what is this? a new teaching—with authority! he commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him” (1:27). The response of amazement occurs also when Jesus heals a paralyzed man (2:12), when the demoniac from the Gerasene tombs declares “how much Jesus had done for him” (5:20), and when he confounded the Pharisees and Herodians with his clever riposte (12:17).

The disciples, walking on the road to Jerusalem, are amazed with the response that Jesus gives to a comment by Peter (10:28–32); as was Pilate, when he presses Jesus to respond to the charges brought against him, but “Jesus made no further reply, so that Pilate was amazed” (15:5).

This synagogue scene not only places Jesus into conflict with the scribes; it also defines the cosmic dimension in which the story of Jesus is set, as he grapples with unclean spirits (1:23–26; 3:11; 5:1–13; 6:7; 7:14–29), also identified as demons (7:24–30; 1:32–34, 39; 3:14–15, 22; 5:14–18; 6:13; 9:38). Jesus is a human being, situated in first century occupied Palestine—but he is engaged in a contest in a cosmic dimension.

Ched Myers offers a compelling interpretation of the scene in the synagogue: “The synagogue on the Sabbath is scribal turf, where they exercise the authority to teach Torah. This “spirit” personifies scribal power, which holds sway over the hearts and minds of the people. Only after breaking the influence of this spirit is Jesus free to begin his compassionate ministry to the masses (1:29ff).”

See https://radicaldiscipleship.net/2015/01/29/lets-catch-some-big-fish-jesus-call-to-discipleship-in-a-world-of-injustice-2/, and the complete commentary on Mark by Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1988).

We may be tempted, today, to look at the way that Jesus operated in these scenes of conflict with “unclean spirits” or “demons” who had possessed a person, and dismiss them as primitive attempts to explain what we now understand as mental illnesses. The many developments in psychology over the last century have certainly enabled us to have a better appreciation of the way the human mind works, and how it meets challenges and disruptions. People possessed by spirits or demons may simply have been people suffering trauma, epilepsy, or psychosis, for instance. And so, we may be tempted to dismiss these exorcisms as unbelievable miracles.

But the approach that Myers takes invites us to give more sober consideration to the structural and societal factors that were at work in these stories. The activity of Jesus was not simply relating to individuals; he was sending a signal to the leaders of his society, confronting them with some of the unpleasant dysfunctions that were the realities for common people living under foreign oppression.

What has generated this conflict from the authorities, and this amazement from the people? It is what Jesus does in the synagogue, when he meets “a man with an unclean spirit” (1:23), who cries out, “what have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth?”, then accuses him, “have you come to destroy us?” (1:24).

Destroy is a very strong word. It is used to describe the conspiracy that is afoot against Jesus from early in the Gospel—after some Pharisees watch Jesus heal a man with a withered hand, and “the Pharisees went out and immediately conspired with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him” (3:6).

And Jesus himself uses this term in a parable, to describe what the owner of the vineyard will do after the tenants kill the slaves, and even the son, sent to them by the owner (12:9). Since the audience of Jerusalem authorities recognise that Jesus “had told this parable against them” (12:12), it is clearly directed at the scribes and other authorities (cf. 11:27).

So, paradoxically, the man with an unclean spirit is aligned with those charged with the responsibility of overseeing the Holiness Code and ensuring that people are “clean”—the scribes and Pharisees, and especially the priests—in articulating this aggressive conflict with Jesus.

And yet, also paradoxically, this unclean man reveals a key matter about Jesus, when he continues, saying, “I know who you are, the Holy One of God” (1:24). It is the spirits and demons in Mark’s narrative who have this insight (see also 3:11; 5:7).

The man calls Jesus “Holy One”. This is a term applied to God in the writings of Hebrew Scripture (Ps 71:22; 78:41; 89:18; Prov 9:10; Job 6:10; Sir 4:14; 23:9; 53:10; 47:8; 48:20) and also by the Prophets (Isa 1:4; 5:19, 24; and a further 24 times; Jer 50:29; Ezek 8:13; Hos 11:9, 12; Hab 1:12; 3:3). It is a central element of who God is, and a key factor in understanding Jesus.

Of course, Holiness was a central element of piety in ancient Israel, exemplified by the Holiness Code of Leviticus (Lev 11:44–45; 19:2; 20:7–8; see also Deut 7:6; 14:2, 21; 28:9). But this man, possessed by an unclean spirit and therefore not in a state of holiness, is able to speak the truth about Jesus as “the Holy One of God”. He was on the edge of society, and yet he was able to perceive a central reality about Jesus and his society. Perhaps it might be our experience, that people on the edge of society are able to see things with a clearer perspective, and illuminate central,realities of society in our time?

Mark indicates that when Jesus instructs the spirit to “be silent, and come out of him!” (1:25), the man is “convulsing him and crying with a loud voice” (1:26). Convulsions caused by a spirit leaving a possessed person are evident also in the scene immediately after the Transfiguration of Jesus, when that spirit “convulsed the boy, and he fell on the ground and rolled about, foaming at the mouth” (9:20).

Such convulsions may perhaps have been associated, in the mind of first century Jews, with King Saul, after he has been defeated by the Philistines (1 Sam 31:1–3). Sensing what this meant for him, Saul took his own life (1 Sam 31:4). One of Saul’s troops escaped the battle; he recounted to David how Saul had implored that man, “come, stand over me and kill me; for convulsions have seized me, and yet my life still lingers” (2 Sam 1:9).

In the modern mind, these convulsions are known to be a part of the medical condition of epilepsy, so we assume that both Saul, the spirit-possessed people in Capernaum, and the spirit- possessed boy in Galilee, were each afflicted with this condition. The healing that Jesus performs appeared impressive to those present; “he commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him” (Mark 1:25–26).

Yet, curiously, the acclamation of the crowd relates, not to the healing powers of Jesus, but to his words of instruction: “what is this? a new teaching—with authority!” (1:27). Neither the details of this teaching, nor the actual process of drawing out the spirit, are recounted in this scene; simply, “Jesus rebuked him” (1:25). It is from this time that “his fame began to spread throughout the surrounding region of Galilee” (1:28).

And so Jesus is followed by crowds in Galilee (2:4, 13; 3:9, 20, 32; 4:1, 36; 5:21–34; 6:34, 45; 7:14, 17; 8:34; 9:14–17, 25), in the Decapolis (7:33; 8:1–9), in Jericho (10:46), and in Jerusalem (11:8, 18, 32; 12:12, 37). The tragedy of the last days of Jesus is acted out in front of crowds of people, when he is arrested (14:43) and brought before Pilate (15:6–15); by implication, numbers of people witness his crucifixion (15:29–32, 40–42).

But the crowds in Capernaum, early in his public ministry, have witnessed him at the height of his powers. And the man in the synagogue, impaired by his condition, has taken us right to the heart of who Jesus is, and what he is doing as he travels around Galilee.