The Iranian Revolution at 30

The Iranian Revolution at 30

The Iranian Revolution at 30

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

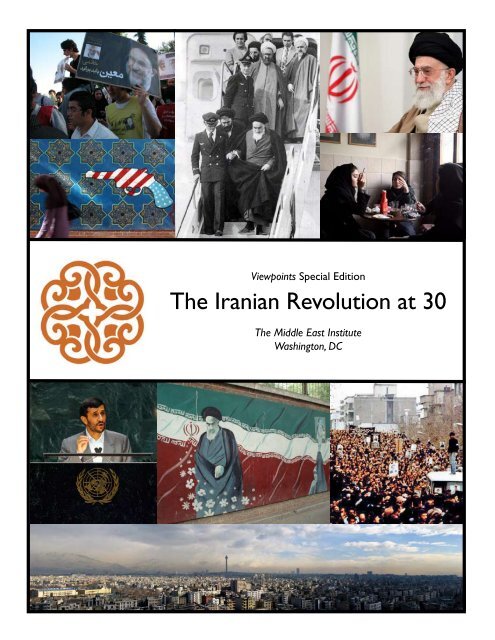

Viewpoints Special Edition<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute<br />

Washington, DC

Middle East Institute<br />

<strong>The</strong> mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in America<br />

and strengthen understanding of the United St<strong>at</strong>es by the people and governments of the<br />

region.<br />

For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the st<strong>at</strong>e<br />

of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It provides<br />

a vital forum for honest and open deb<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong>tracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy<br />

experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders<br />

in countries throughout the region. Along with inform<strong>at</strong>ion exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis,<br />

and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and public<strong>at</strong>ions help counter simplistic notions about the Middle<br />

East and America. We are <strong>at</strong> the forefront of priv<strong>at</strong>e sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service<br />

to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rel<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

with the region.<br />

To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website <strong>at</strong> http://www.mideasti.org<br />

Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Shahram Sharif photo; sajed.ir photo; sajed.ir photo; ? redo photo; sajed.<br />

ir photo; Maryam Ashoori photo; Zongo69 photo; UN photo; and [ john ] photo.<br />

2 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Viewpoints Special Edition<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

3

<strong>The</strong> year 1979 was among the most tumultuous, and important, in the history of the modern Middle East. <strong>The</strong> Middle<br />

East Institute will mark the <strong>30</strong> th anniversary of these events in 2009 by launching a year-long special series of our ac-<br />

claimed public<strong>at</strong>ion, Viewpoints, th<strong>at</strong> will offer perspectives on these events and the influence which they continue to<br />

exert on the region today. Each special issue of Viewpoints will combine the diverse commentaries of policymakers and<br />

scholars from around the world with a robust complement of st<strong>at</strong>istics, maps, and bibliographic inform<strong>at</strong>ion in order<br />

to encourage and facilit<strong>at</strong>e further research. Each special issue will be available, free of charge, on our website, www.<br />

mideasti.org.<br />

In the first of these special editions of Viewpoints, we turn our <strong>at</strong>tention to the <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>, one of the most im-<br />

portant — and influential — events in the region’s recent history. This issue’s contributors reflect on the significance of<br />

the <strong>Revolution</strong>, whose ramific<strong>at</strong>ions continue to echo through the Middle East down to the present day.<br />

February<br />

Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

August<br />

Viewpoints: Oil Shock<br />

Viewpoints: 1979<br />

March<br />

Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> Egyptian-Israeli<br />

Peace Tre<strong>at</strong>y<br />

November<br />

Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> Seizure of the<br />

Gre<strong>at</strong> Mosque<br />

Don’t miss an issue!<br />

Be sure to bookmark www.mideasti.org today.<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

July<br />

Viewpoints: Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s<br />

Fall and Pakistan’s New Direction<br />

December<br />

Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> Soviet Invasion of<br />

Afghanistan

Dedic<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong><br />

A Special Edition of Viewpoints<br />

by Andrew Parasiliti 10<br />

Understanding <strong>Iranian</strong> Foreign Policy,<br />

by R.K. Ramazani 12<br />

I. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> Reconsidered<br />

After the Tehran Spring, by Kian Tajbakhsh 16<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> of February 1979, by Homa K<strong>at</strong>ouzian 20<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>30</strong> Years On, by Shahrough Akhavi 23<br />

<strong>The</strong> Three Paradoxes of the Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> in Iran,<br />

by Abbas Milani 26<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>ary Legacy: A Contested and Insecure Polity,<br />

by Farideh Farhi 29<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong>: Still Unpredictable, by Charles Kurzman 32<br />

<strong>The</strong> Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> Derailed, by Hossein Bashiriyeh 35<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>’s Mixed Balance Sheet, by Fereshtehsad<strong>at</strong> Etefaghfar 39<br />

Between Pride and Dissapointment, by Michael Axworthy 41<br />

II. Inside Iran<br />

Women<br />

Women and <strong>30</strong> Years of the Islamic Republic, by Nikki Keddie 46<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

5

Women and the Islamic Republic: Emancip<strong>at</strong>ion or Suppression?<br />

by F<strong>at</strong>emeh Etemad Moghadam 49<br />

Where Are Iran’s Working Women?<br />

by Valentine M. Moghadam 52<br />

Social Change, the Women’s Rights Movement, and the Role of Islam,<br />

by Azadeh Kian 55<br />

New Challenges for <strong>Iranian</strong> Women, by Elaheh Koolaee 58<br />

Educ<strong>at</strong>ion, Media, and Culture<br />

Educ<strong>at</strong>ional Attainment in Iran, by Zahra Mila Elmi 62<br />

Attitudes towards the Internet in an <strong>Iranian</strong> University,<br />

by Hossein Godazgar 70<br />

Literary Voices, by Nasrin Rahimieh 74<br />

Communic<strong>at</strong>ion, Media, and Popular Culture in Post-revolutionary Iran,<br />

by Mehdi Sem<strong>at</strong>i 77<br />

Society<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> Society: A Surprising Picture, by Bahman Baktiari 80<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ionalism Rediscovered, by Ali Ansari 83<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> “Exceptionalism”, by Sadegh Zibakalam 85<br />

Energy, Economy, and the Environment<br />

Potentials and Challenges in the <strong>Iranian</strong> Oil and Gas Industry,<br />

by Narsi Ghorban 89<br />

Iran’s Foreign Policy and the Iran-Pakistan-India Gas Pipeline,<br />

by Jalil Roshandel 92<br />

Environmental Snaphots in Contemporary Iran,<br />

by Mohammad Eskandari 95<br />

6 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Back to the Future: Bazaar Strikes, Three Decades after the <strong>Revolution</strong>,<br />

by Arang Keshavarzian 98<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> Para-governmental Organiz<strong>at</strong>ions (bonyads), by Ali A. Saeidi 101<br />

Poverty and Inequality since the <strong>Revolution</strong>, by Djavad Salehi-Isfahani 104<br />

Government and Politics<br />

Elections as a Tool to Sustain the <strong>The</strong>ological Power Structure,<br />

by Kazem Alamdari 109<br />

Shi‘a Politics in Iran after <strong>30</strong> Years of <strong>Revolution</strong>, by Babak Rahimi 112<br />

Muhammad Kh<strong>at</strong>ami: A Dialogue beyond Paradox,<br />

by Wm Scott Harrop 115<br />

Minorities<br />

Religious Apartheid in Iran, by H.E. Chehabi 119<br />

Azerbaijani Ethno-n<strong>at</strong>ionalism: A Danger Signal for Iran,<br />

by Daneil Heradstveit 122<br />

III. Regional and Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Rel<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

Sources and P<strong>at</strong>terns of Foreign Policy<br />

Iran’s Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Rel<strong>at</strong>ions: Pragm<strong>at</strong>ism in a <strong>Revolution</strong>ary Bottle,<br />

by Anoush Ehteshami 127<br />

Culture and the Range of Options in Iran’s Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Politics,<br />

by Hossein S. Seifzadeh 1<strong>30</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Geopolitical Factor in Iran’s Foreign Policy,<br />

by Kayhan Barzegar 134<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> Foreign Policy: Concurrence of Ideology and Pragm<strong>at</strong>ism,<br />

by Nasser Saghafi-Ameri 136<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

7

Iran’s Tactical Foreign Policy Rhetoric, by Bidjan Nash<strong>at</strong> 139<br />

<strong>The</strong> Regional <strong>The</strong><strong>at</strong>er<br />

<strong>The</strong> Kurdish Factor in Iran-Iraq Rel<strong>at</strong>ions, by Nader Entessar 143<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong>-Lebanese Shi‘ite Rel<strong>at</strong>ions,<br />

by Roschanack Shaery-Eisenlohr 146<br />

<strong>The</strong> Syrian-<strong>Iranian</strong> Alliance, by Raymond Hinnebusch 149<br />

Twists and Turns in Turkish-<strong>Iranian</strong> Rel<strong>at</strong>ions,<br />

by Mustafa Kibaroglu 152<br />

<strong>The</strong> Dichotomist Antagonist Posture in the Persian Gulf,<br />

by Riccardo Redaelli 155<br />

Iran and the Gulf Cooper<strong>at</strong>ion Council, by Mehran Kamrava 158<br />

Iran and Saudi Arabia: Eternal “Gamecocks?”, by Henner Fürtig 161<br />

<strong>The</strong> Global Arena<br />

<strong>The</strong> European Union and Iran, by Walter Posch 165<br />

Iran and France: Sh<strong>at</strong>tered Dreams, by Pirooz Izadi 168<br />

<strong>The</strong> Spectrum of Perceptions in Iran’s Nuclear Issue,<br />

by Rahman G. Bonab 172<br />

Iran’s Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> and Its Future,<br />

by Abbas Maleki 175<br />

Maps 178<br />

St<strong>at</strong>istics<br />

Demographics 188<br />

8 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Economy 191<br />

Energy 196<br />

Gender 199<br />

Political Power Structure 201<br />

From the Pages of <strong>The</strong> Middle East Journal’s “Chronology:”<br />

Iran in 1979 205<br />

Selected Bibliography 223<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

9

Dedic<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

Andrew Parasiliti<br />

It is only fitting th<strong>at</strong> “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong>” begin with an introductory essay<br />

by R.K. Ramazani and th<strong>at</strong> this project be dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to him. For 55 years, Professor Ramazani<br />

has been a teacher and mentor to many scholars and practitioners of the Middle<br />

East. His body of work on Iran is unrivalled in its scope and originality. Many of his<br />

articles and books on <strong>Iranian</strong> foreign policy are standard works.<br />

For over a quarter century, Dr. Ramazani also has written with eloquence and conviction<br />

of the need for the United St<strong>at</strong>es and Iran to end their estrangement and begin direct<br />

diplom<strong>at</strong>ic talks. Ramazani has no illusions about overcoming three decades of animosity,<br />

but he believes th<strong>at</strong> reconciling US-Iran differences is vital to resolving America’s<br />

other str<strong>at</strong>egic challenges in the Middle East — including in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the<br />

Israeli-Palestinian conflict — and to bringing sustainable peace and security to the<br />

region.<br />

Professor Ramazani’s service to both the Middle East Institute and to the University of<br />

Virginia has been recognized time and again. As one of Dr. Ramazani’s former students,<br />

and as a former director of programs <strong>at</strong> MEI, I can personally <strong>at</strong>test to his deep commitment<br />

to both institutions. His life-long contribution to the Middle East Institute was<br />

recognized <strong>at</strong> MEI’s Annual Conference in October 1997, when he was presented with<br />

the Middle East Institute Award. Currently, Dr. Ramazani serves with distinction on<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Journal’s Board of Advisory Editors. At the University of Virginia, his<br />

teaching and scholarship embodied Thomas Jefferson’s precept for the University th<strong>at</strong><br />

“Here we are not afraid to follow truth, wherever it may lead, nor toler<strong>at</strong>e any error so<br />

long as reason is left free to comb<strong>at</strong> it.”<br />

It is in th<strong>at</strong> spirit th<strong>at</strong> this volume is dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to R. K. Ramazani.<br />

Andrew Parasiliti is Principal,<br />

Government Affairs-<br />

Intern<strong>at</strong>ional, <strong>at</strong> <strong>The</strong> BGR<br />

Group in Washington, DC.<br />

From 2001-2005, he was<br />

foreign policy advisor to US<br />

Sen<strong>at</strong>or Chuck Hagel (R-<br />

NE). Dr. Parasiliti received a<br />

Ph.D. from the Paul H. Nitze<br />

School of Advanced Intern<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

Studies, Johns Hopkins<br />

University, and an MA from<br />

the University of Virginia. He<br />

has served twice as director<br />

of programs <strong>at</strong> the Middle<br />

East Institute.<br />

10 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Dedic<strong>at</strong>ion...<br />

A Chronology of Dr. Ramazani’s articles in <strong>The</strong> Middle East Journal<br />

“Afghanistan and the USSR,” Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring 1958)<br />

“Iran's Changing Foreign Policy: A Preliminary Discussion,” Vol. 24, No. 4 (Autumn 1970)<br />

“Iran's Search for Regional Cooper<strong>at</strong>ion,” Vol. <strong>30</strong>, No. 2 (Spring 1976)<br />

“Iran and <strong>The</strong> United St<strong>at</strong>es: An Experiment in Enduring Friendship,” Vol. <strong>30</strong>, No. 3 (Summer<br />

1976)<br />

“Iran and the Arab-Israeli Conflict,” Vol. 32, No. 4 (Autumn 1978)<br />

“Who Lost America? <strong>The</strong> Case of Iran,” Vol. 36, No. 1 (Winter 1982)<br />

“Iran's Foreign Policy: Contending Orient<strong>at</strong>ions,” Vol. 43, No. 2 (Spring 1989)<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Islamic Republic of Iran: <strong>The</strong> First 10 Years (Editorial),” Vol. 43, No. 2 (Spring 1989)<br />

“Iran's Foreign Policy: Both North and South,” Vol. 46, No. 3 (Summer 1992)<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Shifting Premise of Iran's Foreign Policy: Towards a Democr<strong>at</strong>ic Peace?” Vol. 52, No. 2<br />

(Spring 1998)<br />

“Ideology and Pragm<strong>at</strong>ism in Iran's Foreign Policy,” Vol. 58, No. 4 (Autumn 2004)<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

Former MEI President<br />

Roscoe Suddarth<br />

presents Dr. Ramazani<br />

with the 1997 Middle<br />

East Institute Award.<br />

11

Understanding <strong>Iranian</strong> Foreign Policy<br />

R.K. Ramazani<br />

Understanding Iran’s foreign policy is the key to crafting sensible and effective policies<br />

toward Iran and requires, above all, a close analysis of the profound cultural and<br />

psychological contexts of <strong>Iranian</strong> foreign policy behavior.<br />

For Iran, the past is always present. A paradoxical combin<strong>at</strong>ion of pride in <strong>Iranian</strong> cul-<br />

ture and a sense of victimiz<strong>at</strong>ion have cre<strong>at</strong>ed a fierce sense of independence and a culture<br />

of resistance to dict<strong>at</strong>ion and domin<strong>at</strong>ion by any foreign power among the <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

people. <strong>Iranian</strong> foreign policy is rooted in these widely held sentiments.<br />

THE RooTS oF IRANIAN FoREIGN PolICy<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong>s value the influence th<strong>at</strong> their ancient religion, Zoroastrianism, has had on Judaism,<br />

Christianity, and Islam. <strong>The</strong>y take pride in <strong>30</strong> centuries of arts and artifacts, in<br />

the continuity of their cultural identity over millennia, in having established the first<br />

world st<strong>at</strong>e more than 2,500 years ago, in having organized the first intern<strong>at</strong>ional society<br />

th<strong>at</strong> respected the religions and cultures of the people under their rule, in having<br />

liber<strong>at</strong>ed the Jews from Babylonian captivity, and in having influenced Greek, Arab,<br />

Mongol, and Turkish civiliz<strong>at</strong>ions — not to mention having influenced Western culture<br />

indirectly through <strong>Iranian</strong> contributions to Islamic civiliz<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

At the same time, however, <strong>Iranian</strong>s feel they have been oppressed by foreign powers<br />

throughout their history. <strong>The</strong>y remember th<strong>at</strong> Greeks, Arabs, Mongols, Turks, and most<br />

recently Saddam Husayn’s forces all invaded their homeland. <strong>Iranian</strong>s also remember<br />

th<strong>at</strong> the British and Russian empires exploited them economically, subjug<strong>at</strong>ed them<br />

politically, and invaded and occupied their country in two World Wars.<br />

<strong>The</strong> facts th<strong>at</strong> the United St<strong>at</strong>es aborted <strong>Iranian</strong> democr<strong>at</strong>ic aspir<strong>at</strong>ions in 1953 by over-<br />

throwing the government of Prime Minister Muhammad Musaddeq, returned the autocr<strong>at</strong>ic<br />

Shah to the throne, and thereafter domin<strong>at</strong>ed the country for a quarter century is<br />

deeply seared into Iran’s collective memory. Likewise, just as the American overthrow of<br />

Musaddeq was etched into the <strong>Iranian</strong> psyche, the <strong>Iranian</strong> taking of American hostages<br />

in 1979 was engraved into the American consciousness. Iran’s rel<strong>at</strong>ions with the United<br />

St<strong>at</strong>es have been shaped not only by a mutual psychological trauma but also by collective<br />

memory on the <strong>Iranian</strong> side of 70 years of amicable Iran-US rel<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

R.K. Ramazani is Professor<br />

Emeritus of Government<br />

and Foreign Affairs <strong>at</strong> the<br />

University of Virginia. He<br />

has published extensively on<br />

the Middle East, especially<br />

on Iran and the Persian Gulf,<br />

since 1954, and has been<br />

consulted by various US administr<strong>at</strong>ions,<br />

starting with<br />

th<strong>at</strong> of former President Jimmy<br />

Carter during the <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

hostage crisis in 1979-1981.<br />

12 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Ramazani...<br />

In spite of these historical wounds, <strong>Iranian</strong>s remember American support of their first <strong>at</strong>tempt to establish a democr<strong>at</strong>ic<br />

represent<strong>at</strong>ive government in 1905-1911; American championing of Iran’s rejection of the British bid to impose a protector<strong>at</strong>e<br />

on Iran after World War I; American support of Iran’s resistance to Soviet pressures for an oil concession in<br />

the 1940s; and, above all else, American efforts to protect Iran’s independence and territorial integrity by pressuring the<br />

Soviet Union to end its occup<strong>at</strong>ion of northern Iran <strong>at</strong> the end of World War II.<br />

A TRADITIoN oF PRUDENT STATECRAFT<br />

Contrary to the Western and Israeli depiction of <strong>Iranian</strong> foreign policy as “irr<strong>at</strong>ional,” Iran has a tradition of prudent<br />

st<strong>at</strong>ecraft th<strong>at</strong> has been cre<strong>at</strong>ed by centuries of experience in intern<strong>at</strong>ional affairs beginning with Cyrus the Gre<strong>at</strong> more<br />

than 2,000 years ago.<br />

To be sure, Iran has made many mistakes in its long diplom<strong>at</strong>ic history. In the postrevolutionary<br />

period, and particularly in the early years of the Islamic revolution, Iran’s<br />

foreign policy was often characterized by provoc<strong>at</strong>ion, agit<strong>at</strong>ion, subversion, taking<br />

of hostages, and terrorism. Most recently, Iran’s intern<strong>at</strong>ional image was tarnished by<br />

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s imprudent rhetoric about Israel and the Holocaust<br />

in disregard of the importance of intern<strong>at</strong>ional legitimacy and the <strong>Iranian</strong>-Islamic dictum<br />

of hekm<strong>at</strong> (wisdom).<br />

Yet it is also important to acknowledge instances where post-revolutionary <strong>Iranian</strong> foreign policy has been moder<strong>at</strong>e<br />

and constructive. Ahmadinejad’s predecessor, President Mohammad Kh<strong>at</strong>ami, vehemently denounced violence and<br />

terrorism, promoted détente, pressed for “dialogue among civiliz<strong>at</strong>ions,” improved Iran’s rel<strong>at</strong>ions with its Persian Gulf<br />

neighbors, reversed Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s f<strong>at</strong>wa against author Salman Rushdie, bettered rel<strong>at</strong>ions with Europe,<br />

softened Iran’s adversarial <strong>at</strong>titude toward Israel, and, above all, offered an “olive branch” to the United St<strong>at</strong>es. His<br />

foreign policy restored the tradition of hekm<strong>at</strong> (wisdom) to Iran’s st<strong>at</strong>ecraft.<br />

lESSoNS To BE lEARNED<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are valuable lessons to be learned by countries th<strong>at</strong> deal with Iran, especially those powers th<strong>at</strong> are quarreling with<br />

Iran over the crucial nuclear issue.<br />

First, Iran’s st<strong>at</strong>ecraft is inextricably linked to the expect<strong>at</strong>ion of respect. In <strong>at</strong>tempting to negoti<strong>at</strong>e with Iran, pressures<br />

and thre<strong>at</strong>s, direct or indirect, military, economic or diplom<strong>at</strong>ic, can prove highly counterproductive. When the United<br />

St<strong>at</strong>es says “all the options are on the table” in the nuclear dispute, for example, Iran views this as a thre<strong>at</strong> of military<br />

force th<strong>at</strong> must be resisted. Or when the six powers issued their joint proposal to Iran for discussion, as they did in Geneva<br />

on July 19, 2008, with an August 2 deadline for an <strong>Iranian</strong> response, Iran understood it as an ultim<strong>at</strong>um th<strong>at</strong> could<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

In <strong>at</strong>tempting to<br />

negoti<strong>at</strong>e with<br />

Iran, pressures and<br />

thre<strong>at</strong>s, direct or<br />

indirect, military,<br />

economic or diplom<strong>at</strong>ic,<br />

can prove<br />

highly counterproductive.<br />

13

Ramazani...<br />

be followed by the imposition of gre<strong>at</strong>er sanctions.<br />

While Iran’s reaction to the Geneva meeting, which included the United St<strong>at</strong>es for the first time, was generally positive,<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> leaders said enough to demonstr<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> they expect respect and reject thre<strong>at</strong>s. In addressing the <strong>Iranian</strong> people<br />

on the critical nuclear issue on July 17, 2008, the <strong>Iranian</strong> Supreme Leader, Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Ali Khamene’i, rejected thre<strong>at</strong>s<br />

from the United St<strong>at</strong>es, saying th<strong>at</strong> “[t]he <strong>Iranian</strong> people do not like thre<strong>at</strong>s. We will not respond to thre<strong>at</strong>s in any way.”<br />

Yet he specifically praised the European powers because “they respect the <strong>Iranian</strong> people. <strong>The</strong>y stress th<strong>at</strong> they respect<br />

the rights of the <strong>Iranian</strong> people.”<br />

Following Khamene’i, on July 28, 2008 President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad told the anchor<br />

of NBC Nightly News, “You know full well th<strong>at</strong> nobody can thre<strong>at</strong>en the <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

people and pose [a] deadline they expect us to meet.” He rejected the August 2 deadline<br />

on the same day and said on August 3, “Iran has always been willing to solve the longstanding<br />

crisis over its disputed nuclear program through negoti<strong>at</strong>ions.” Reportedly,<br />

Iran would make its own proposal in its own time, perhaps on August 5.<br />

Second, Iran’s interlocutors would benefit significantly if they also understood Iran’s<br />

negoti<strong>at</strong>ing style. Cre<strong>at</strong>ed, molded, and honed by long diplom<strong>at</strong>ic experience, <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

diplom<strong>at</strong>s combine a range of tactics in dealing with their counterparts: testing, probing,<br />

procrastin<strong>at</strong>ing, exagger<strong>at</strong>ing, bluffing, ad-hocing, and counter-thre<strong>at</strong>ening when<br />

thre<strong>at</strong>ened.<br />

Third, foreign powers such as the United St<strong>at</strong>es should recognize the fierce sense of independence and resistance of<br />

the <strong>Iranian</strong> people, regardless of political and ideological differences, to direct or indirect pressure, dict<strong>at</strong>ion, and the<br />

explicit or implied thre<strong>at</strong> of force. With these points in mind, American leaders can still draw cre<strong>at</strong>ively on the historic<br />

reservoir of <strong>Iranian</strong> goodwill toward the United St<strong>at</strong>es to craft initi<strong>at</strong>ives th<strong>at</strong> will be well received in Iran.<br />

THE WAy FoRWARD FoR THE UNITED STATES<br />

Cre<strong>at</strong>ed, molded,<br />

and honed by long<br />

diplom<strong>at</strong>ic experience,<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> diplom<strong>at</strong>s<br />

combine<br />

a range of tactics<br />

in dealing with<br />

their counterparts:<br />

testing, probing,<br />

procrastin<strong>at</strong>ing,<br />

exagger<strong>at</strong>ing, bluffing,<br />

ad-hocing, and<br />

counter-thre<strong>at</strong>ening<br />

when thre<strong>at</strong>ened.<br />

<strong>The</strong> United St<strong>at</strong>es should recognize the legitimacy of the <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> unequivocally. <strong>The</strong> United St<strong>at</strong>es should<br />

also assess realistically Iran’s projection of power in the Middle East, particularly in the Persian Gulf, where Iran seeks<br />

acknowledgment of its role as a major player. Thirdly, the US administr<strong>at</strong>ion should reconsider its reliance on more<br />

than three decades of containment and sanctions, which have not weakened the regime, but have grievously harmed the<br />

<strong>Iranian</strong> people, whom America claims to support. Finally, the United St<strong>at</strong>es should also talk to Iran unconditionally. On<br />

the nuclear issue in particular, the United St<strong>at</strong>es should take up Iran on its explicit commitment to uranium enrichment<br />

solely for peaceful purposes, and President Ahmadinejad’s st<strong>at</strong>ement th<strong>at</strong> “Iran has always been willing to resolve the<br />

nuclear dispute through negoti<strong>at</strong>ions.”<br />

14 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

I. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> Reconsidered<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

15

After the Tehran Spring<br />

Kian Tajbakhsh<br />

Ten years ago, in the summer of 1998, I arrived in Tehran after an absence of more<br />

than two decades. Three vignettes describe some of wh<strong>at</strong> I experienced and why I decided<br />

to stay.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mayor. I am in a shared taxi with an architect friend who is pointing out some re-<br />

cent developments in the city. We are squeezed in the front passenger se<strong>at</strong>, three men in<br />

the back. <strong>The</strong> taxi’s radio is on, and all are listening intently to the live broadcast of the<br />

trial of Tehran’s high profile and dynamic mayor, Gholamhosein Karbaschi, the Robert<br />

Moses of Tehran, was on trial on thin charges of embezzlement, although most believed<br />

it was political retribution for contributing to Muhammad Kh<strong>at</strong>ami’s 1996 presidential<br />

election victory. Judge: “Is it not true th<strong>at</strong> you controlled a number of personal accounts<br />

and moved money around them thereby viol<strong>at</strong>ing financial laws?” Taxi Driver breaks<br />

in: “Agghhh! Th<strong>at</strong> Karbaschi! He’s lining his pockets just like all the others. Wh<strong>at</strong> has he<br />

done for this city all these years? Nothing! Absolutely nothing!”<br />

We break through some gnarled traffic and enter a wide urban highway winding down<br />

around several hillocks, all bright green, full of flowerbeds, sprinklers busy, a big clock<br />

sculpted into the face in rocks and plants. My architect friend: “This is a brand new road<br />

system opened only a few months ago. It has finally connected two parts of the city<br />

and eased the flow from the west to the north of the city. <strong>The</strong> landscaping? Oh th<strong>at</strong>’s<br />

standard for almost all urban redevelopment.” On hearing this, the Taxi Driver broke in<br />

again: “Are you kidding me? (so to speak). Th<strong>at</strong> Karbaschi is a genius! I should know. I<br />

drive all day. Before him this city was a mess, it was unlivable. All these new roads are<br />

gre<strong>at</strong> and the city has turned a new leaf.” L<strong>at</strong>er when I had decided to write a book on<br />

urban policy and local government in Iran I always reminded myself th<strong>at</strong> pinning down<br />

wh<strong>at</strong> ordinary people thought about their city would not be straightforward!<br />

<strong>The</strong> Park. An old friend calls <strong>at</strong> about 10 pm: “want to go for a spin? You’ll see something<br />

of the city too.” “Well, ye s… but isn’t it l<strong>at</strong>e?” Friend arrives <strong>at</strong> 11:<strong>30</strong>. By midnight<br />

we are <strong>at</strong> Park-e Mell<strong>at</strong> (the People’s Park) the largest in the city. With difficulty we find<br />

a parking space, the entire area is jammed with cars and people. “We’re going into the<br />

park now?” (Anyone who lived in New York in the 1980s would understand the incredulity.)<br />

But of course we entered — like the hundreds, yes hundreds of large extended<br />

families with small children carrying blankets, gas cookers, huge pots of food, canisters<br />

of tea. <strong>The</strong> we<strong>at</strong>her is superb. Families are laying around, children playing ball or bad-<br />

Kian Tajbakhsh works as an<br />

intern<strong>at</strong>ional consultant in<br />

the areas of local government<br />

reform, urban planning, social<br />

policy, and social science<br />

research. Dr. Tajbakhsh has<br />

consulted for several intern<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

organiz<strong>at</strong>ions such<br />

as the World Bank, the Netherlands<br />

Associ<strong>at</strong>ion of Municipalities<br />

(VNG-Int.) and<br />

the open Society Institute.<br />

He received his M.A. from<br />

University College, london<br />

in 1984, and a Ph.D. from<br />

Columbia University, New<br />

york City in 1993.<br />

16 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Tajbakhsh...<br />

minton, boys and girls easily straying from their parents, each feeling safe enough with all the “eyes on the street.” <strong>The</strong><br />

night is warm. Young couples are holding hands on benches slightly out of sight, in the row bo<strong>at</strong>s on the little artificial<br />

lake. And me? My mouth wide open in disbelief <strong>at</strong> this idyllic urban scene: a public space supplied by a conscientious<br />

municipality and dedic<strong>at</strong>ed designers, used civilly and politely by huge numbers of people from many classes. Many,<br />

judging by their chadors and rougher clothes, were from the poorer parts of the city — this was a family outing, perhaps<br />

the next day was a holiday. “But when — in fact how — would they go to work?” I ask. <strong>The</strong> city is dotted with smaller<br />

parks, just as much used.<br />

People have nothing else to do! We decide to see the movie everyone is talking about,<br />

Tahmineh Milani’s Two Women. But every the<strong>at</strong>er we try is sold out. We have to wait<br />

two weeks to get a ticket. “This is amazing,” I say, “such a vibrant cultural life.” “Oh,” M<br />

replies, “because of the government restrictions people don’t have anything else to do,<br />

so they all pour into the cinemas.” (mardom tafrih-e digeh nadarand.) (I do finally see<br />

the film — it is powerful and important.) It is suggested instead th<strong>at</strong> we go to the traditional<br />

local restaurants in the foothills of Darband. <strong>The</strong> description seems too good to<br />

be true: Persian carpets spread among trees and running streams in a mountain village<br />

20 minutes north of the city, serving Persian food and tea amidst the cool mountain<br />

air; elegant women reclining on large cushions and so on. <strong>The</strong> orientalist in me thoroughly<br />

(and unashamedly) awakened, we head off … to a traffic jam about a mile long.<br />

<strong>The</strong> road entering the village is backed up with cars, some ordinary, some expensive.<br />

We hear th<strong>at</strong> restaurants have waits of over an hour. (<strong>The</strong> New Yorker in me groans “not here too?”) Defe<strong>at</strong>ed we turn<br />

back. “I would never have imagined anything like this,” I say. “Oh,” M replies, “it’s because people don’t have any other<br />

opportunities for recre<strong>at</strong>ion.” Next: the the<strong>at</strong>er. Only a friend who has connections can swing, with gre<strong>at</strong> difficulty, some<br />

tickets for the first of Mirbagheri’s play cycle. <strong>The</strong> st<strong>at</strong>ely City <strong>The</strong><strong>at</strong>er is full of people who have come to see the plays,<br />

some also to see and be seen, a perfectly acceptable objective. I want a ticket for the next play, but we have to join a long<br />

waiting list and may not make it. (We don’t in fact succeed.) “Th<strong>at</strong>’s the way it is, unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely,” M observes, “people just<br />

don’t have any other distractions, so they have to come to the the<strong>at</strong>er.”<br />

At this point I fall in love with the city. I decide to find a way to come back and, if possible, stay. So I did move to Tehran,<br />

first and foremost for personal reasons. I studied Persian classical music, met my current wife — we now have a little<br />

baby girl. I made many deep and meaningful friendships, which means, when we converse I feel th<strong>at</strong> it is about something.<br />

At the same time, the convers<strong>at</strong>ion is always embedded in very human rel<strong>at</strong>ions, about the interaction in ways I<br />

never learned in New York. I soon became involved in intellectual deb<strong>at</strong>es raging during the reform period, and once or<br />

twice got into trouble with the authorities.<br />

Professionally, for the last ten years I have been working, teaching, and researching the newly emerging world of <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

cities and local governments. Unlikely though it sounds, elected city councils several years ago emerged as a key<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

My mouth wide<br />

open in disbelief<br />

<strong>at</strong> this idyllic urban<br />

scene: a public<br />

space supplied by<br />

a conscientious<br />

municipality and<br />

dedic<strong>at</strong>ed designers,<br />

used civilly and politely<br />

by huge numbers<br />

of people from<br />

many classes.<br />

17

Tajbakhsh...<br />

b<strong>at</strong>tleground for new visions for society and governance. I quickly became involved in the work of newly established<br />

councils, worked on the laws, was asked for advice (occasionally, I was able to give some), engaged in intern<strong>at</strong>ional public<br />

diplomacy, organizing several exchanges between European and <strong>Iranian</strong> mayors. Most fulfilling was learning about<br />

Iran’s cities and towns and peoples through traveling to dozens of cities across the country. Only now, ten years on, do<br />

I feel I have something to say about the hopes for local democracy th<strong>at</strong> were part of the reform agenda — arguably the<br />

most important institutional legacy of the reform period.<br />

Ten years l<strong>at</strong>er, the “Long Tehran Spring” is over. Wh<strong>at</strong> I initially thought was the beginning<br />

of the “Spring” when I arrived to stay in 2001, was, in retrospect, the downturn<br />

towards its end. Wh<strong>at</strong> I didn’t realize <strong>at</strong> the time was th<strong>at</strong> the Tehran th<strong>at</strong> I experienced<br />

represented for another group of <strong>Iranian</strong>s a neg<strong>at</strong>ive and unwelcome image of social<br />

life. By 1990, with the grueling war with Iraq over, reconstruction was underway. Every<br />

Tehrani will tell you th<strong>at</strong> Karbaschi transformed the capital from a morbid monument<br />

to the war dead — in the somber idiom of Shi‘a martyrdom — into a city in which life<br />

was affirmed through parks full of flowers and entertainment, where young couples<br />

could, discretely, entwine fingers and feel the pleasures of being alive, bookshops were accessible where one could<br />

browse the books, music cassettes, and CDs unavailable in the previous decade; a city which tried to be a more efficient<br />

and user friendly place for getting to work, for producing goods and services of everyday and banal use; in which brand<br />

new street lights would be efficient as well as a boost to the morale of residents, who could feel th<strong>at</strong> th<strong>at</strong> they were no<br />

longer living in a war-affected place. All this was desper<strong>at</strong>ely needed, especially by young middle class Tehranis who<br />

had lived through a decade of war and were now young university students and wanted to stretch their legs in a city<br />

connected to global currents and excitements.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se two groups<br />

— the urban young<br />

middle class and<br />

the lower-class war<br />

veterans — clashed<br />

on the streets of<br />

Tehran in the 1990s.<br />

But then millions of others had been involved directly in fighting the war, and tens of thousands of poor, mostly rural,<br />

families had counted their children among the war dead. <strong>The</strong>y also came to Tehran, because after all, it was also their<br />

city. <strong>The</strong>y brought with them a more burdened conscience; conserv<strong>at</strong>ive, small town beliefs and values; sometimes Puritan<br />

morality as a means of honoring the memory of those who had died as well as their own experience; most of those<br />

who had volunteered, often without pay, to fight to defend their families, friends and country — and survived — they<br />

had suffered a decade of lost educ<strong>at</strong>ion, m<strong>at</strong>erial progress, and savings.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se two groups — the young urban middle class and the lower-class war veterans — clashed on the streets of Tehran<br />

in the 1990s. <strong>The</strong> former wanted to put the war behind them; the l<strong>at</strong>ter surely could not so soon. Besides the memories,<br />

there was the sense on one side th<strong>at</strong> the veterans deserved help in return for protecting the country and thus providing<br />

the tranquility th<strong>at</strong> it appeared some younger Tehranis now took for granted. On the other side, there emerged a sense<br />

of resentment against the affirm<strong>at</strong>ive action for the families of veterans, who some viewed as cynically exploiting their<br />

st<strong>at</strong>us to cash in on free refriger<strong>at</strong>ors and guaranteed college admission. This conflict was daringly portrayed in the film<br />

Glass Agency. Complic<strong>at</strong>ing m<strong>at</strong>ters, hostility and resentment l<strong>at</strong>ched easily onto the m<strong>at</strong>ter of sexuality, especially in<br />

18 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Tajbakhsh...<br />

public, and particularly around women. By the end of the post-war decade, the second group had obtained their degrees,<br />

gained professional experience in the bureaucracy, and was finally able to demand a se<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong> the table. Of course,<br />

some want the table itself, and are even making a bid for all the other chairs!<br />

So the capital city is one, perhaps the arena in which an important set of challenges for<br />

the future of Iran is being played out. <strong>The</strong> Tehran municipality has been a disappointment,<br />

as have all elected local governments, who with the waning of n<strong>at</strong>ional reform<br />

energies, have settled into being another sub-office of the governmental bureaucracy.<br />

With significant and ostensibly non-governmental resources, it has missed a chance to<br />

be the forum for Tehran’s residents. This challenge is <strong>at</strong> bottom a cultural and a n<strong>at</strong>ional<br />

one — wh<strong>at</strong> will be the values th<strong>at</strong> define the n<strong>at</strong>ion, who will we be? As yet, the city<br />

contains multitudes only numerically. <strong>The</strong> challenge is to transform the city from the<br />

b<strong>at</strong>tleground it often feels like, to a canvass on which a moral vision th<strong>at</strong> can accept the<br />

conflicting values can form themselves into some kind of p<strong>at</strong>tern th<strong>at</strong> all, or <strong>at</strong> least<br />

most, can recognize and understand. We still occasionally go to the movies, the the<strong>at</strong>er,<br />

and the hills. But more and more time is spent inside our homes. Wh<strong>at</strong> the city needs<br />

most is the élan I felt th<strong>at</strong> summer ten years ago.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

<strong>The</strong> challenge is to<br />

transform the city<br />

from the b<strong>at</strong>tleground<br />

it often feels<br />

like, to a canvass on<br />

which a moral vision<br />

th<strong>at</strong> can accept<br />

the conflicting values<br />

can form themselves<br />

into some<br />

kind of p<strong>at</strong>tern th<strong>at</strong><br />

all, or <strong>at</strong> least most,<br />

can recognize and<br />

understand.<br />

19

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> of February 1979<br />

Homa K<strong>at</strong>ouzian<br />

<strong>The</strong> revolution of February 1979 was a revolt of the society against the st<strong>at</strong>e. In some<br />

of its basic characteristics, the revolution did not conform to the usual norms of Western<br />

revolutions, because the st<strong>at</strong>e did not represent just an ordinary dict<strong>at</strong>orship but an<br />

absolute and arbitrary system th<strong>at</strong> lacked political legitimacy and a social base virtually<br />

across the whole of the society.<br />

This became a puzzle to some in the West, resulting in their disappointment and disillusionment<br />

within the first few years of the revolution’s triumph. For them, as much<br />

as for a growing number of modern <strong>Iranian</strong>s who themselves had swelled the street<br />

crowds shouting pro-Khomeini slogans, the revolution became “enigm<strong>at</strong>ic,” “bizarre,”<br />

and “unthinkable.”<br />

In the words of one Western scholar, the revolution was “deviant” because it established<br />

an Islamic republic and also since “according to social-scientific explan<strong>at</strong>ions for revolution,<br />

it should not have happened <strong>at</strong> all, or when it did.” Th<strong>at</strong> is why large numbers of<br />

disillusioned <strong>Iranian</strong>s began to add their voice to the Shah and the small remnants of<br />

his regime in putting forward conspiracy theories — chiefly and plainly th<strong>at</strong> America<br />

(and / or Britain) had been behind the revolution in order to stop the shah pushing for<br />

higher oil prices. It was even said th<strong>at</strong> the West had been afraid th<strong>at</strong> economic development<br />

under the Shah would soon rob it of its markets.<br />

Before the fall of the Shah’s regime, this “puzzle” of the <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> was somewh<strong>at</strong><br />

closed to the eyes of Western observers. All the signs had been there, but they were<br />

largely eclipsed by the massive peaceful processions, the solidarity and virtual unanimity<br />

of the society to overthrow the st<strong>at</strong>e, and the blood sacrifice. <strong>The</strong>y were eclipsed also<br />

by the phenomenon of Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Ruhollah Khomeini, every one of whose words was<br />

received as divine inspir<strong>at</strong>ion by the gre<strong>at</strong> majority of <strong>Iranian</strong>s — modern as well as<br />

traditional.<br />

It is certainly possible to make sense of <strong>Iranian</strong> revolutions by utilizing the tools and<br />

methods of the same social sciences th<strong>at</strong> have been used in explaining Western revolutions.<br />

However, explan<strong>at</strong>ions of <strong>Iranian</strong> revolutions th<strong>at</strong> are based on the applic<strong>at</strong>ion of<br />

such tools and methods to Western history inevitably result in confusion, contradiction,<br />

and bewilderment. As Karl Popper once noted, there is no such thing as History; there<br />

Homa K<strong>at</strong>ouzian, St Antony’s<br />

College and Faculty of<br />

oriental Studies, University<br />

of oxford<br />

20 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

K<strong>at</strong>ouzian...<br />

are histories. <strong>The</strong> most obvious point of contrast is th<strong>at</strong> in Western revolutions, the societies in question were divided,<br />

and it was the underprivileged classes th<strong>at</strong> revolted against the privileged classes, who were most represented by the<br />

st<strong>at</strong>e. In both the traditional and the modern <strong>Iranian</strong> revolutions, however, the whole society — rich and poor — revolted<br />

against the st<strong>at</strong>e.<br />

From the Western perspective, it would certainly make no sense for some of the richest classes of the society to finance<br />

and organize the movement, while a few of the others either sit on the fence or believe th<strong>at</strong> it was America’s doing and<br />

could not be helped. Similarly, it would make no sense by Western criteria for the entire st<strong>at</strong>e appar<strong>at</strong>us (except the<br />

military, which quit in the end) to go on an indefinite general strike, providing the most potent weapon for the success<br />

of the revolution. Nor would it make sense for almost the entire intellectual community and modern educ<strong>at</strong>ed groups<br />

to rally behind Khomeini and his call for Islamic government.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 1979 revolution was a characteristically <strong>Iranian</strong> revolution — a revolution by the<br />

whole society against the st<strong>at</strong>e in which various ideologies were represented, the most<br />

dominant being those with Islamic tendencies (Islamist, Marxist-Islamic and democr<strong>at</strong>ic-Islamic)<br />

and Marxist-Leninist tendencies (Fada’i, Tudeh, Maoist, Trotskyist, and<br />

others). <strong>The</strong> conflict within the groups with Islamic and Marxist-Leninist tendencies<br />

was probably no less intense than th<strong>at</strong> between the two tendencies taken together. Yet<br />

they were all united in the overriding objective of bringing down the shah and overthrowing<br />

the st<strong>at</strong>e. More effectively, the mass of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion who were not strictly<br />

ideological according to any of these tendencies — and of whom the modern middle<br />

classes were qualit<strong>at</strong>ively the most important — were solidly behind the single objective<br />

of removing the Shah. Any suggestion of a compromise was tantamount to treason.<br />

Moreover, if any settlement had been reached short of the overthrow of the monarchy,<br />

legends would have grown as to how the liberal bourgeoisie had stabbed the revolution<br />

in the back on the order of their “foreign [i.e. American and British] masters.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> most widespread and commonly held slogan th<strong>at</strong> united the various revolutionary parties and their supporters<br />

regardless of party and program was “Let him [the Shah] go and let there be flood afterwards” (In beravad va har cheh<br />

mikhahad beshavad). Many changed their minds in the following years, but nothing was likely to make them see things<br />

differently <strong>at</strong> the time. Thirty years l<strong>at</strong>er, Ebrahim Yazdi, a leading assistant of Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Paris<br />

and l<strong>at</strong>er Foreign Minister in the post-revolutionary provisional government, was reported in Washington as speaking<br />

“candidly of how his revolutionary gener<strong>at</strong>ion had failed to see past the short-term goal of removing the Shah...”<br />

Those who lost their lives in various towns and cities throughout the revolution certainly played a major part in the<br />

process. But the outcome would have been significantly different if the commercial and financial classes, which had<br />

reaped such gre<strong>at</strong> benefits from the oil bonanza, had not financed the revolution; or especially if the N<strong>at</strong>ional <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

It would make no<br />

sense by Western<br />

criteria for the entire<br />

st<strong>at</strong>e appar<strong>at</strong>us<br />

(except the military,<br />

which quit in the<br />

end) to go on an<br />

indefinite general<br />

strike, providing<br />

the most potent<br />

weapon for the success<br />

of the revolution.<br />

21

K<strong>at</strong>ouzian...<br />

Oil Company employees, high and low civil servants, judges, lawyers, university professors, intellectuals, journalists,<br />

school teachers, students, etc., had not joined in a general strike; or if the masses of young and old, modern and traditional,<br />

men and women, had not manned the huge street columns; or if the military had united and resolved to crush<br />

the movement.<br />

<strong>The</strong> revolutions of 1906-1909 and 1977-1979 look poles apart in many respects. Yet they<br />

were quite similar with regard to some of their basic characteristics, which may also<br />

help explain many of the divergences between them. Both were revolts of the society<br />

against the st<strong>at</strong>e. Merchants, traders, intellectuals, and urban masses played a vital role<br />

in the Constitutional <strong>Revolution</strong> of 1906-1909, but so did leading ‘ulama’ and powerful<br />

landlords, such th<strong>at</strong> without their active support the triumph of 1909 would have been<br />

difficult to envisage — making it look as if “the church” and “the feudal-aristocr<strong>at</strong>ic<br />

class” were leading a “bourgeois democr<strong>at</strong>ic revolution”! In th<strong>at</strong> revolution, too, various<br />

political movements and agendas were represented, but they were all united in the aim<br />

of overthrowing the arbitrary st<strong>at</strong>e (and ultim<strong>at</strong>ely Muhammad ‘Ali Shah), which stood<br />

for traditionalism, so th<strong>at</strong> most of the religious forces also rallied behind the modernist<br />

cause, albeit haphazardly.<br />

Many of the traditional<br />

forces<br />

backing the<br />

Constitutional<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> regretted<br />

it after the<br />

event, as did many<br />

of the modernists<br />

who particip<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

in the revolution<br />

of February 1979,<br />

when the outcome<br />

ran contrary to<br />

their own best<br />

hopes and wishes.<br />

Many of the traditional forces backing the Constitutional <strong>Revolution</strong> regretted it after the event, as did many of the<br />

modernists who particip<strong>at</strong>ed in the revolution of February 1979, when the outcome ran contrary to their own best<br />

hopes and wishes. But no argument would have made them withdraw their support before the collapse of the respective<br />

regimes. <strong>The</strong>re were those in both revolutions who saw th<strong>at</strong> total revolutionary triumph would make some, perhaps<br />

many, of the revolutionaries regret the results afterwards, but very few of them dared to step forward. Sheikh Fazlollah<br />

in the earlier case and Shahpur Bakhtiar in the l<strong>at</strong>er are noteworthy examples. But they were both doomed because they<br />

had no social base, or in other words, they were seen as having joined the side of the st<strong>at</strong>e, however hard they denied it.<br />

In a revolt against an arbitrary st<strong>at</strong>e, whoever wants anything short of its removal is branded a traitor. Th<strong>at</strong> is the logic<br />

of the slogan “Let him go and let there be flood afterwards!”<br />

22 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>30</strong> Years On<br />

Shahrough Akhavi<br />

In assessing the progress of the revolution in Iran, it might be useful to recall how other<br />

revolutions of the 20 th century fared <strong>at</strong> the <strong>30</strong>-year interval. Using their commence-<br />

ment r<strong>at</strong>her than the actual seizure of power as the baseline, the <strong>30</strong> th anniversaries of<br />

major 20 th century revolutions were 1940 for Mexico, 1947 for the Soviet Union, 1964<br />

for China (using the “Long March” as the year), 1975 for Vietnam, 1983 for Cuba (d<strong>at</strong>ing<br />

its beginning with the <strong>at</strong>tack on the Moncada Barracks), 1984 for Algeria, and 2008<br />

for Nicaragua.<br />

It was only with Lazaro Cardenas’s tenure (1934-1940) th<strong>at</strong> the early land reforms demanded<br />

by the Zap<strong>at</strong>istas were finally pushed through. Meanwhile, many of the revolution’s<br />

leaders had been assassin<strong>at</strong>ed. In the Soviet case, Josef Stalin’s grip on power<br />

became so suffoc<strong>at</strong>ing th<strong>at</strong> many argue th<strong>at</strong> by 1947 the promises of the Russian <strong>Revolution</strong><br />

not only had not been fulfilled, but the country had even retrogressed. For China,<br />

1964 came shortly after the disastrous “Gre<strong>at</strong> Leap Forward” of 1958 and the concomitant<br />

radical People’s Communes policies, which were harbingers of the coming excesses<br />

of the Cultural <strong>Revolution</strong> launched in 1966. In Vietnam, 1975 marked the pullout of<br />

the American military and the unific<strong>at</strong>ion of the country under the post-Ho Chi Minh<br />

(d. 1969) leadership. This marked a major political victory, but economically the country<br />

was in a shambles. In 1983, Cuba, despite very impressive achievements in areas<br />

such as health care and educ<strong>at</strong>ion, faced a precarious economic situ<strong>at</strong>ion, thanks in<br />

large measure to the American embargo but also internal mismanagement. In Algeria,<br />

as 1984 dawned, the st<strong>at</strong>e’s reput<strong>at</strong>ion was mainly as a leader of the non-aligned movement<br />

and of the Group of 77 in the United N<strong>at</strong>ions. But serious economic troubles accompanying<br />

the regime’s version of socialism undermined these diplom<strong>at</strong>ic successes.<br />

Nicaragua was a seeming exception to these cases, as contested elections took place<br />

in 1990, with the Sandinista regime voluntarily relinquishing power to a coalition of<br />

bourgeois political parties. In 2006 Daniel Ortega was elected President, marking the<br />

return of the Sandinista leader to power. <strong>The</strong> Citizen Power Councils introduced under<br />

his leadership proved controversial, but on the whole the society seemed to be moving<br />

away from the politics of violence.<br />

Wh<strong>at</strong> about the Islamic Republic of Iran? Regionally, it has become a leading power, but<br />

this is not due to the efforts of the leadership. It has instead resulted from the Americanled<br />

invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, which removed the <strong>Iranian</strong> government’s two<br />

major regional enemies: the Ba‘th and the Taliban. So far, Iran’s nuclear program has<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

Dr. Shahrough Akhavi, University<br />

of South Carolina<br />

23

Akhavi...<br />

r<strong>at</strong>tled the West and Israel, and the Arab st<strong>at</strong>es also are unhappy about it. So far, thre<strong>at</strong>s from the United St<strong>at</strong>es and Israel<br />

have not resulted in armed conflict, but internal sabotage through the infiltr<strong>at</strong>ion of “black ops” detachments and<br />

unmanned aircraft strikes are frequently rumored to have occurred or to be in store.<br />

However, it is in internal developments th<strong>at</strong> the <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> faces its major shortcomings and failures on its <strong>30</strong> th<br />

anniversary. <strong>The</strong> ever-widening gap between st<strong>at</strong>e and society is no secret to observers. This gap was a serious problem<br />

in the l<strong>at</strong>e Pahlavi period. Although it was temporarily narrowed in the early post-revolutionary period (due in significant<br />

measure to Iraq’s invasion of Iran, which caused regime opponents to “rally to the flag”), it grew dram<strong>at</strong>ically when<br />

the Khomeinists launched a kulturkrieg against the intellectuals and the universities after June 1981, a struggle th<strong>at</strong><br />

continues today. This has led to serious defections not only on the part of the secular-but-religious-minded intellectuals<br />

— such as ‘Abd al-Karim Surush, Akbar Ganji, and Sa‘id Hajjarian — but also by leading thinkers of the traditional<br />

seminaries, such as Muhsin Kadivar and ‘Abdallah Nuri among lower ranking seminarians, and Mahdi Ha‘iri (d. 1999),<br />

Sadiq Ruhani, and Husayn ‘Ali Muntaziri among senior clerics. As for secular-oriented intellectuals, they too have faced<br />

intimid<strong>at</strong>ion, though some, such as film directors, have been given a surprising degree of l<strong>at</strong>itude.<br />

<strong>The</strong> several governments since 1979 have failed in their promises to diversify the econ-<br />

<strong>The</strong> several governomy<br />

and thus end the country’s over-dependence on oil. Over time, the economy has ments since 1979<br />

performed poorly. <strong>The</strong> current regime had staked its reput<strong>at</strong>ion on improving the lives have failed in their<br />

of the masses, but, if anything, it has proven itself more incompetent than its predeces- promises to diversors.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Khomeinists have reacted by clinging even more tightly to power. <strong>The</strong> leader, sify the economy<br />

‘Ali Khamane‘i, in advance of the next presidential elections (now scheduled for June and thus end the<br />

2009), has tried to pre-empt the outcome by telling the current incumbent, Mahmud country’s over-dependence<br />

on oil.<br />

Ahmadinejad, to prepare for another term in office. <strong>The</strong> June 2009 voting will mark the<br />

tenth presidential election since 1980, suggesting a degree of institutionaliz<strong>at</strong>ion. But in<br />

fact it seems th<strong>at</strong> the pre-determining of the outcome of such elections remains an abiding issue. This is not to suggest<br />

th<strong>at</strong> sometimes presidential outcomes do appear to be the result of an open electoral process, but this is the exception<br />

(for example, the presidential elections of 1997 and 2001).<br />

However, dram<strong>at</strong>ic improvements have been shown in literacy; advances in health care are evident, and in principle,<br />

women are not barred from high office. In the early 1980’s Khomeini issued a f<strong>at</strong>wa against factory owners who were<br />

trying to deny female employees m<strong>at</strong>ernity leave and thus sided with women’s economic rights. Recently, it has been<br />

noted in the press th<strong>at</strong> the judicial authorities have ruled th<strong>at</strong>, <strong>at</strong> least for now, the capital sentence of stoning be suspended<br />

until exemplary justice becomes not just the norm but the reality, so th<strong>at</strong> its viol<strong>at</strong>ion would be inexcusable.<br />

Nevertheless, the balance sheet in regard to human rights is strongly neg<strong>at</strong>ive. An estim<strong>at</strong>ed 150 newspapers have been<br />

shut down since the revolution, leading public figures are routinely harassed and imprisoned, the authorities arbitrarily<br />

reject candid<strong>at</strong>es for office (even those whom they permitted to run in earlier campaigns), and they send armed thugs<br />

24 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Akhavi...<br />

into people’s homes, places of work, classrooms, and open assembly venues to wreak havoc in defense of the absolute<br />

mand<strong>at</strong>e of the jurist (Velayet-e Faqih). Perhaps, despite certain achievements, it is the f<strong>at</strong>e of all revolutions to suffer<br />

<strong>The</strong>rmidorean reactions, as Crane Brinton once noted. 1 This could be said to varying<br />

degrees of the Mexican, Russian, Chinese, Vietnamese, Cuban, Algerian, and Nicara- <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong><br />

guan revolutions. Although a hallmark of <strong>The</strong>rmidor is the end of the extreme brutality <strong>Revolution</strong> is <strong>30</strong><br />

years old, but it still<br />

of the reign of terror and virtue, another characteristic is the return to the authoritarian<br />

suffers a plethora<br />

excesses of the past. For its part, the <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> is <strong>30</strong> years old, but it still suffers<br />

of “infantile disor-<br />

a plethora of “infantile disorders.” <strong>The</strong>rmidor is “alive and well” in the Islamic Republic ders.”<br />

of Iran. It is its society th<strong>at</strong> is the loser.<br />

1. <strong>The</strong> term “<strong>The</strong>rmidor” refers to the revolt against the excesses of the French <strong>Revolution</strong>. See Crane Brinton’s classic study<br />

<strong>The</strong> An<strong>at</strong>omy of <strong>Revolution</strong>, revised edition (New York: Vintage, 1965).<br />

<strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org<br />

25

<strong>The</strong> Three Paradoxes of the Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> in Iran<br />

Abbas Milani<br />

<strong>The</strong> Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> of 1979 is an event defined as much by its ironies and paradoxes<br />

as by its novelties and cruelties.<br />

It was, by scholarly near-consensus, the most “popular revolution” in modern times —<br />

almost 11% of the popul<strong>at</strong>ion particip<strong>at</strong>ed in it, compared to the approxim<strong>at</strong>e 7% and<br />

9% of the citizens who took part in the French and Russian revolutions. As a concept,<br />

revolution is itself a child of modernity, in th<strong>at</strong> it revolves around the idea th<strong>at</strong> legiti-<br />

m<strong>at</strong>e power can eman<strong>at</strong>e only from a social contract consecr<strong>at</strong>ed by the general will of<br />

Abbas Milani is the Hamid<br />

a sovereign people. Before the rise of modernity and the idea of the n<strong>at</strong>ural rights of and Christina Moghadam<br />

human beings, “revolution” as a word had no political connot<strong>at</strong>ion and simply referred Director of <strong>Iranian</strong> Studies<br />

to the movement of celestial bodies. <strong>The</strong> word took on its new political meaning — the<br />

<strong>at</strong> Stanford University where<br />

he is also a Research Fellow<br />

sudden, often violent, structural change in the n<strong>at</strong>ure and distribution of power and <strong>at</strong> the Hoover Institution.<br />

privilege — when the idea of a citizenry (imbued with n<strong>at</strong>ural rights, including the right His most recent book, Emi-<br />

to decide who rules over them) replaced the medieval idea of “subjects” (a passive popunent Persians: <strong>The</strong> Men and<br />

Women who Made Modern<br />

lace, bereft of rights, deemed needful of the guardianship of an aristocracy or royalty).<br />

Iran, 1941-1979 (two volumes)<br />

was just published by<br />

In Iran, despite the requisite popular agency of a revolution, events in 1979 paradoxi- Syracuse University Press.<br />

cally gave rise to a regime wherein popular sovereignty was denigr<strong>at</strong>ed by the regime’s<br />

founding f<strong>at</strong>her, Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Ruhollah Khomeini, as a colonial construct, cre<strong>at</strong>ed to undermine<br />

the Islamic concept of umma (or spiritual community). In Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Khomeini’s<br />

tre<strong>at</strong>ise on Islamic government, the will of the people is subservient to the dict<strong>at</strong>es of<br />

the divine, as articul<strong>at</strong>ed by the Supreme Leader. In this sense, his concept of an Islamic<br />

<strong>Revolution</strong> is an oxymoron and its concomitant idea of Islamic government — velay<strong>at</strong>e<br />

faqih, or rule of the Jurist — is irreconcilable with the modern democr<strong>at</strong>ic ideal of<br />

popular sovereignty. On the contrary, velay<strong>at</strong>-e faqih posits a popul<strong>at</strong>ion in need of a<br />

guardian, much as minors need guardians. <strong>The</strong> people are, in other words, “subjects,” not<br />

citizens. On the other hand, he called the same populace to a revolution —historically,<br />

the defiant act of a citizenry cognizant of its ability and right to demand a new social<br />

contract. <strong>The</strong> most popular of all “modern revolutions” then led to the cre<strong>at</strong>ion of a st<strong>at</strong>e<br />

whose constitution places absolute power in the hand of an unelected, unimpeachable<br />

man, and whose basic political philosophy posits people as subjects and pliable tools of<br />

the Faqih. If this constitutes the philosophical paradox of the Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong>, there<br />

is also a stark historic paradox evident in its evolution.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Islamic <strong>Revolution</strong> was in a sense a replay of Iran’s first assay <strong>at</strong> a democr<strong>at</strong>ic con-<br />

26 <strong>The</strong> Middle East Institute Viewpoints: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Iranian</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong> <strong>at</strong> <strong>30</strong> • www.mideasti.org

Milani...<br />

stitutional government, one th<strong>at</strong> took place in the course of the 1905-07 “Constitutional <strong>Revolution</strong>.” At th<strong>at</strong> time, a coalition<br />

of secular intellectuals, enlightened Shi‘ite clergy, bazaar merchants, the rudiments of a working class, and even<br />

some members of the landed gentry came together to topple the Oriental Despotism of the Qajar kings and replace it<br />

with a monarchy whose power was limited by a constitution (Mashruteh). Indeed, the new constitution emul<strong>at</strong>ed one<br />

of the European models of a liberal democr<strong>at</strong>ic polity, one th<strong>at</strong> allowed for elections and separ<strong>at</strong>ion of powers, yet had<br />

a monarch as the head of the st<strong>at</strong>e. In those years, the most ideologically cohesive and powerful opposition to this new<br />

democr<strong>at</strong>ic paradigm was spearheaded by Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Nouri — a Shi‘ite zealot who dismissed modern, democr<strong>at</strong>ically<br />

formul<strong>at</strong>ed constitutions as the faulty and feeble concoctions of “syphilitic men.” Instead, he suggested relying on wh<strong>at</strong><br />

he considered the divine infinite wisdom of God, manifest in Shari’a (Mashrua’). So powerful were the advoc<strong>at</strong>es of the<br />

constitutional form of democracy th<strong>at</strong> Nouri became the only ay<strong>at</strong>ollah in Iran’s modern history to be executed on the<br />

order (f<strong>at</strong>wa) of fellow ay<strong>at</strong>ollahs. For decades, in Iran’s modern political discourse, Nouri’s name was synonymous with<br />

the reactionary political creed of despots who sought their legitimacy in Shi‘ite Shari’a.<br />

In a profoundly paradoxical twist of politics, almost 70 years l<strong>at</strong>er, the same coalition<br />

of forces th<strong>at</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ed the constitutional movement, coalesced once again, this time to<br />

topple the Shah’s authoritarian rule. Each of the social classes constituting th<strong>at</strong> coalition<br />

had, by the 1970s, become stronger, and more politically experienced. Nevertheless,<br />

they chose as their leader Ay<strong>at</strong>ollah Khomeini, a man who espoused an even more<br />

radical version of Shari’a-based politics than the one proposed by Nouri. While Nouri<br />

had simply talked of a government based on Shari’a (Mashrua’), Khomeini now advoc<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

the absolute rule of a man whose essential claim to power rested in his mastery<br />

of Shari’a, and for whom Sharia was not the end but a means of power. In the decade<br />

before the revolution, some secular <strong>Iranian</strong> intellectuals like al-Ahmad, imbued with<br />

the false certitudes of a peculiar brand of radical anti-colonial politics paved the way<br />

for this kind of clerical regime by “rehabilit<strong>at</strong>ing” Nouri and offering a revisionist view<br />