- For decades, it’s been theorized the Great Sphinx of Giza may have originally been a lion-shaped natural landform that ancient Egyptians modified to form the stone-faced feline.

- A new study from the New York University uses fluid dynamics to analyze if the creation of a such a shape via wind erosion is possible.

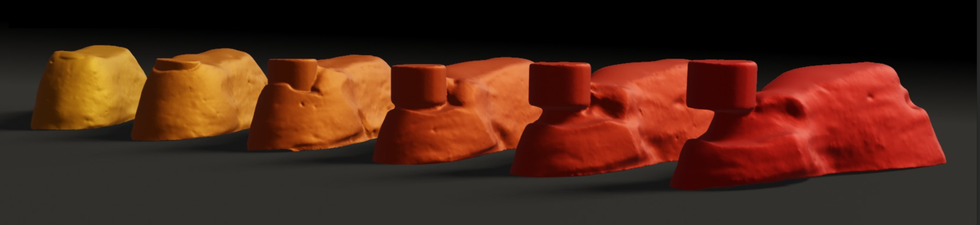

- Creating many mounds of bentonite clay and plastic (a stand-in for compact clay known as yardangs) and using running water to simulate wind erosion, the team discovered that a lion-like shape could form naturally.

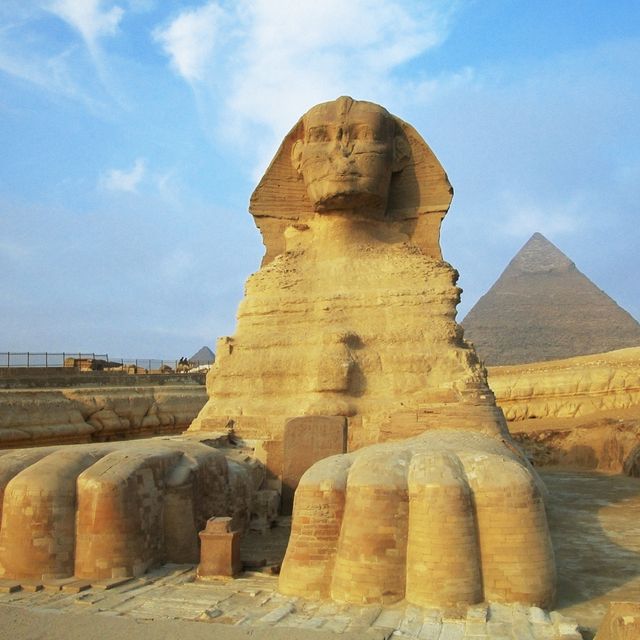

The Great Pyramids of Giza are arguably the most impressive construction project of the ancient world as some 2.3 million limestone slabs make up the Great Pyramid alone, but another majestic symbol along the Nile—the Great Sphinx of Giza—has a more mysterious origin story.

In a 1981 Smithsonian Magazine article, geologist Farouk El-Baz theorizes that the ancient Egyptians didn’t create the sphinx from scratch, like the pyramids, but that desert winds formed the overall contours of the sphinx and the ancient stonemasons gave the rock a celestial face lift.

Now, scientists from New York University have tested that theory by creating miniature, lion-like landforms from clay using fluid dynamics and discovered that it’s possible that the shape of the rock inspired Egyptians to create the sphinx. Their work has been accepted by the journal Physical Review Fluids.

The team, led by New York University’s Leif Ristroph, originally studied how water eroded clay. After building several bentonite clay mounds with non-erodible plastic (standing in for “hard inclusions”) at the upstream end of each one, water flowed over the mounts parallel to its long axis. Over time, the water ate away the clay, but left the non-erodible plastic intact, and Ristroph was struck by the appearance of a very familiar shape.

“We were struck by the resemblance to a seated lion or a lion in repose,” Ristroph told New Scientist. “The fluid is eating away the solid, but the solid then forces the flow to conform to its shape. It feeds back on the flow and changes erosion rates and how it is distributed over the surface.”

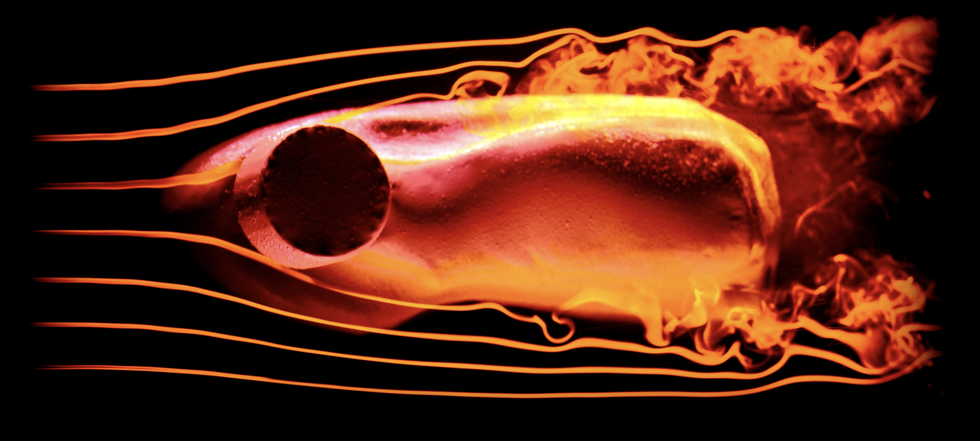

While non-erodible plastic doesn’t exist in nature (or at least, it doesn’t exist naturally), geological features known as yardangs certainly do, which are sharp, irregular ridges of compact sand. Ristroph and his team also added dye to the water to more accurately visualize how winds could have shaped the back of the sphinx if met by a compact yardang upstream.

“Releasing dye upstream reveals compressed streaklines under the head, and this accelerated flow digs the neck and reveals the forelimbs and paws,” Ristroph and his team write in a poster about their findings. “These results show what ancient peoples may have encountered in the deserts of Egypt and why they envisioned a fantastic creature.”

El-Baz originally theorized that ancient Egyptians carved the head of the Sphinx out of a naturally occurring yardang, and Ristroph’s fluid dynamics study appears to lend some compelling evidence to this theory. But whether the Sphinx of Giza is a built-from-scratch masterpiece or a wonder of sculpting nature, its stoic visage will continue inspiring the millions of visitors every year.

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.